Wisdom begins in wonder.

-Socrates

When the first automobiles rolled into public view in the 1890s they were called horseless carriages.

In a 1911 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, Alexander Winton, early inventor, and pioneer of the auto industry reflected on America’s initial skepticism toward the first wave of cars:

The great obstacle to the development of the automobile was the lack of public interest. To advocate replacing the horse, which had served man through centuries, marked one as an imbecile. Things are very different today. But in the ’90s, even though I had a successful bicycle business, and was building my first car in the privacy of the cellar in my home, I began to be pointed out as “the fool who is fiddling with a buggy that will run without being hitched to a horse.

Winton goes on, recalling his banker’s reaction to the “experiment” taking place in his basement:

Winton, I am disappointed in you. You’re crazy if you think this fool contraption you’ve been wasting your time on will ever displace the horse.

To prove that his “fiddling” was not in vain, Winton reached for his pocket and pulled out a clipping from the New York World of November 17, 1895.

It was an interview with Thomas A. Edison.

“Talking of horseless carriage suggests to my mind that the horse is doomed. The bicycle, which, 10 years ago, was a curiosity, is now a necessity. It is found everywhere. Ten years from now you will be able to buy a horseless vehicle for what you would pay today for a wagon and a pair of horses. The money spent in the keep of the horses will be saved and the danger to life will be much reduced.”

“It is only a question of a short time when the carriages and trucks of every large city will be run by motors. The expense of keeping and feeding horses in a great city like New York is very heavy, and all this will be done away with. You must remember that every invention of this kind which is made adds to the general wealth by introducing a new system of greater economy of force. A great invention which facilitates commerce, enriches a country just as much as the discovery of vast hoards of gold.”

The banker threw back the clipping and snorted, “Another inventor talking.”

We know how the story goes from here. Ford, faster horses, and the Model-T.

What Winton, Edison, and Ford did not see — what they couldn’t have seen — was that on the shoulders of their ingenuity, an Ohioan-born test-pilot named Neil Armstrong would, in the same century, stamp his boot-print on the surface of the moon. The iconic image, planted in the collective consciousness of humanity, is a potent reminder that what is possible will always exceed what has been dreamt.

I’ve been thinking about horseless carriages a lot lately. The way history, in spite of innovation, finds a way to repeat itself. How human behavior is, for better or worse, predictable.

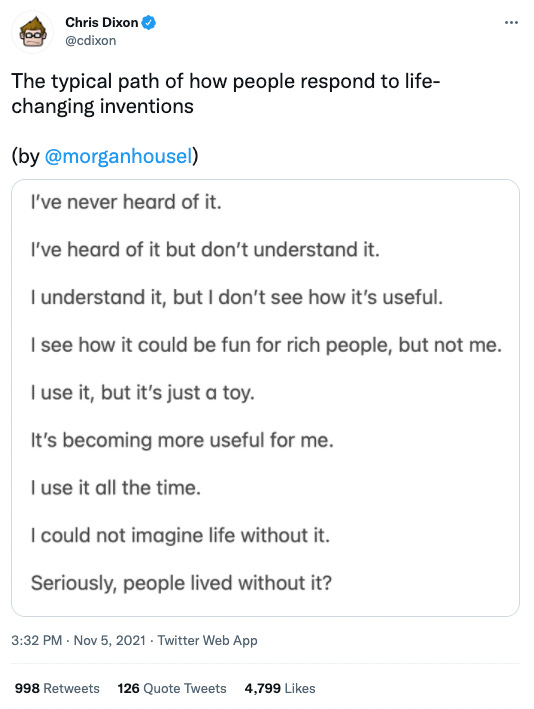

In his essay, doing old things better vs doing brand new things, Chris Dixon (a remarkably prescient web3 thought leader) touches on the psychology of why our ancestors were slow to see beyond the horseless carriage…

Doing old things better tends to get more attention early on because it’s easier to imagine what to build. Early films were shot like plays — they were effectively plays with a better distribution model — until filmmakers realized that movies had their own visual grammar. The early electrical grid delivered light better than gas and candles. It took decades before we got an electricity “app store” — a rich ecosystem of appliances that connected to the grid. The early web was mostly digital adaptations of pre-internet things like letter writing and mail-order commerce. It wasn’t until the 2000s that entrepreneurs started exploring “internet native” ideas like social networking, crowdfunding, cryptocurrency, crowdsourced knowledge bases, and so on.

Chris recently tweeted a distilled version of this idea.

Last week, on the heels of a successful NFT.NYC, Mayor-elect Eric Adams announced on Twitter that he’d be accepting his first three paychecks in Bitcoin — a shrewd political maneuver that capitalized on the momentum while signaling New York as a future hub of blockchain innovation.

To my ears, this was great news. It’s been a tough couple of years for the city. Anyone who’s been there, or was ousted as I was, will tell you as much. The soon-to-be Mayor’s message felt like a step forward.

And then I saw this:

Paul Krugman is a Nobel Laureate and op-ed columnist at the New York Times, which means I’m out credentialed. But hey, it’s my substack, so I’ll bite.

Doomed, Mr. Krugman? Really?

A healthy amount of skepticism is vital for any innovation to bloom. Blind spots and echo chambers are real, which is why discourse is so important. Not hyperbole.

Make no mistake — we are in a period of real innovation. The internet is evolving, updating to a more intelligent, decentralized version of itself. This is a good thing. A natural progression. Should we choose to play our cards right, this is a period that will incentivize creativity, collaboration, and curiosity at unprecedented rates.

Do we really have the hubris to believe there won’t be a technological breakthrough in the next twenty years as drastic as the Printing Press, Model-T, or iPhone? That its effect on society would not be as seismic?

I find Mr. Krugman’s response lacking in imagination.

The morning after Mayor-elect Adams’ fired off the bitcoin tweet, I read a blog post by Morgan Housel, titled The Same Stories, Again and Again.

Housel, who wrote The Psychology Of Money, argues that a common story we’ve told ourselves throughout history is that past innovation was magnificent, but future innovation must be limited because we’ve picked all the low-hanging fruit.

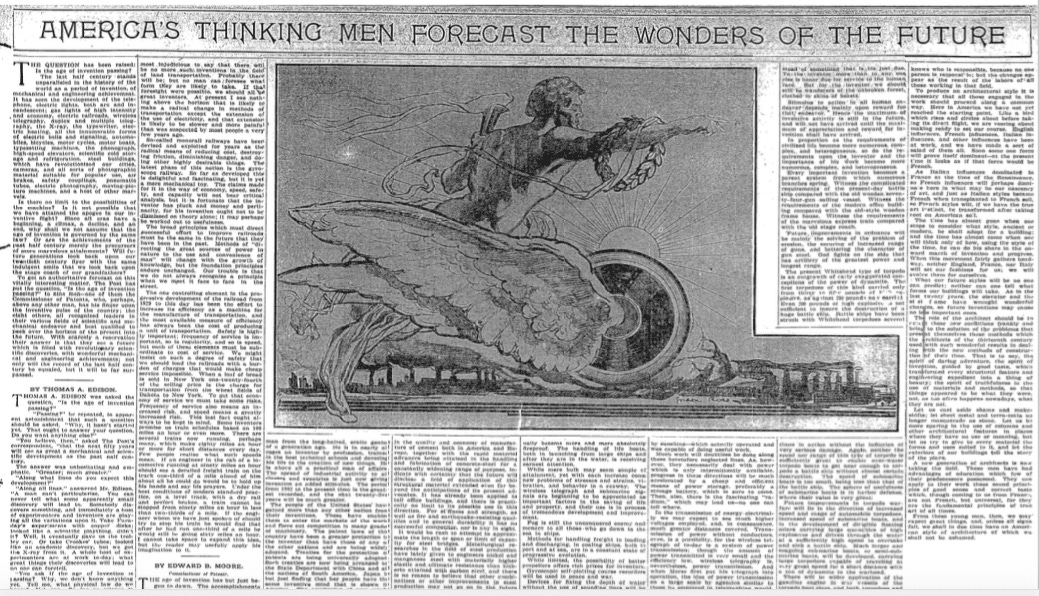

He brings the reader back to January 12th, 1908, when the Washington Post ran a full-page spread called “America’s Thinking Men Forecast the Wonders of the Future.”

One of the “thinking men” interviewed was, again, Thomas Edison.

The Post editors asked: “Is the age of invention passing?”

Edison’s answer was predictable:

“Passing?” he repeated, in apparent astonishment that such a question should be asked.

“Why, it hasn’t started yet. That ought to answer your question. Do you want anything else?”

“You believe, then, that the next 50 years will see as great a mechanical and scientific development as the past half century?” the Post asked Edison.

“Greater. Much greater,” he replied.

“Along what lines do you expect this development?” they asked him.

“Along all lines.”

—

Edison, of course, was right.