The Path of the Wind

A Pilgrim's Tale

The geographical pilgrimage is the symbolic acting out of an inner journey. The inner journey is the interpolation of the meanings and signs of the outer pilgrimage. One can have one without the other. It is best to have both.

- Thomas Merton

I.

I’m half-awake on a stiff mattress in a two-star hotel room off the corner of a cobblestone street. Coarse sheets feel like paper against my perspiring skin. A rusty air-conditioner roars and rattles to life in the corner, oscillating the room’s climate from muggy to frigid in a matter of seconds. Ominous thoughts cloud my mind, and as best as I try to will it, sleep won’t come. My pack’s too heavy. My Spanish? Laughable. I am alone.

I toss and turn some more, flick on a fluorescent lamp, and reach for the journal and pen at my nightstand.

Day 1 — I scribble above the margin of the first blank page — Pamplona.

I’m half awake on a stiff mattress in a two-star hotel room off the corner of a cobblestone street.

II.

I stir out of bed eventually, unsure if I laid claim to any real sleep or if the energy I have is fueled solely by adrenaline. An analog alarm clock shows 6:18 AM.

The shower is creaky and tepid but gets the job done. Temperatures will hover above ninety today, so I throw on a pair of running shorts and a Dri-Fit Nike tee. On my face, forearms, and legs, I lather sunscreen more carefully than I have in years, and tie a bandana around the back of my neck for an added layer of UV protection.

All the prep guides harp the same advice: take care of your feet at all costs. Blisters are part of the experience, they remind you, but too many will jeopardize your chances of making it to Galicia intact. This in mind, I reach in my toiletry bag for the green tube of Hirschtalg — a German foot balm made from deer fat that I picked up the day before at a boutique trekking shop behind Plaza Del Castillo. The shop’s Swedish keeper assured me that if I rubbed the menthol-scented cream on my feet every morning before putting on socks, I’d stroll “blister free” into the hallowed halls of Santiago de Compostela — where, legend has it, the bones of the Apostle James are buried.

On each foot I massage a dab of Hirschtalg, pull-on merino wool socks, and lace up my trail runners, which I double knot. Scanning the room, I cram what’s left of my strewn belongings into a 38-liter Osprey backpack bursting, already, at capacity. Next I grab my hiking poles, cork-handled ones, which the friendly Swede assured me would be easier on my hands than the plastic models. From the Osprey’s side-zipped pocket, I unfurl an LED headlamp, flash it twice, and wrap it around my head like a holy medal before venturing outside. On the way out I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror. I look ridiculous. An over-branded American, jet-lagged and uncaffeinated, nervous like a child on the first day of school. Nevertheless, I can’t help but smirk at my reflection as I leave the room behind.

***

Pamplona is leafy and quaint in September. Cobblestone alleys connect Cypress-lined plazas to main roads and bike lanes. Every summer, as part of the Festival of San Fermín, bulls chase emboldened locals and half-drunk tourists from one side of the city to the other. They end at the stone arena of Plaza de Toros — one of Hemingway’s old domains. It was here that the 26-year-old writer, enamored by the matadors and wine-flowing revelry, was inspired to write The Sun Also Rises. A granite bust of Papa sits at the stadium’s entrance to this day, greeting patrons and passerby pilgrims with a chiseled, steely gaze.

Strolling along, I inhale wafts of café con leche, freshly lit cigarettes, and pastries hot from the oven. Students in brown uniforms scurry between butchers shouldering pigs; fruit vendors stock their stands, whistling. As the city glows to life against the pale emergence of dawn, there is a charm to observe in the flow of things. Pamplonicas, to my eye, appear content.

III.

Nearing the city's end, I stop at a bronze fountain marked with a gold-plated scallop shell, and sit for a minute to take in the scene. Birds sing and banter. Mist evaporates. A cool breeze from the valley cuts the warm rising sun and hints, for a moment, at autumn.

Gathering my bearings for the day ahead, I leaf through A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Camino de Santiago by John Brierley. Brierley’s book, revered among American pilgrims, offers detailed maps of all thirty-three stages that make up the Camino Francés — the most popular of the seven major routes comprising The Way of Saint James.

Each stage, a day’s walk by Brierley’s estimate, gets several pages of maps and diagrams, with notes on things like altitude change, terrain type, landmarks, albergues (hostels for pilgrims), and recommended cafes.

Today’s stage leads to Puente la Reina. A medieval town of less than twenty-five hundred, known for its six-arched Roman bridge from the 11th century that is still in use today. It will be a 24 kilometer walk across the Navarre valley from where I’m standing now. Just under fifteen miles.

A pilgrim travels on two paths simultaneously, Brierley suggests, and must pay equal attention to both.

There is The Practical Path, which, for today’s stage, reads as follows:

The first 5 km is mostly via city pavements and suburban roads which are hard underfoot. But Beyond Cizur Menor we have pathways through the hill pass ahead. This is a steep climb through the middle of the wind turbines, visible on the skyline at Alto del Perdón.

And then there is The Mystical Path, where Brierley switches gears from trail guide to guru:

Will we notice the beehives? He begins. Each home to thousands of bees that collect nectar from the almond blossom that grace this fertile plain in the springtime. In the winter all is laid bare and the hives lie dormant awaiting a time of renewal.

I like Brierley. He’s got a way of spurring spiritual introspection without forcing it down your throat. Take, for instance, the curious tidbit he plants in the guide’s preface:

Recent surveys indicate that Spain, until recently a deeply religious society, now has less than 20% of its population practicing a form of organized religion, yet here is the rub - in this same ten-year period of steep decline the numbers entering the Camino de Santiago have soared, rising tenfold in a decade.

How, wonders Brierley, do we interpret these trends?

IV.

Before moving on from the fountain, I hear a shuffle from behind and glimpse a brawny, bespectacled figure barreling toward me like a pack mule. Drawn to his directional conviction, I offer an amicable wave. When our paths converge, I spot a white scallop shell dangling by twine from his faded black JanSport. I notice he’s limping quite badly too.

“Blisters, mate,” he says in lieu of a greeting. “Bloody bad ones.” With a wince he offers me an outstretched hand.

“Name’s Liam.”

“Good to meet you, man,” I say as we shake hands. “I’m Nick. From New York.”

Liam’s tall and sturdy and speaks with a kindly Irish brogue. His face reminds me of Ronan Tynan, the Irish tenor who was always on TV after 9/11 belting God Bless America at Yankees games. Liam looks like he’s in his early thirties, around the same age as me.

I tell him it’s my first day walking.

“No kidding,” he responds warmly. “Allow me to wish you your first Buen Camino then.”

I thank him and nod toward his hiking boots.

“Should’ve worn the trail runners,” he says, noticing mine regretfully. “I’m a dunce and didn’t break ‘em in before crossing the Pyrenees. Suppose I’ll need to swap them out for a size up soon.”

Liam drops his bag next to mine and splashes water from the fountain on his face. I can tell he’s hurting.

“Shall we get on with it then?” he suggests after a few minutes of small talk. “Better to cover distance early, beat the worst of the heat. The nicer albergues usually fill up by three, so the earlier you check in the better your chances are of scoring a decent bunk.”

Grateful for the tip, I tell Liam I’ll follow him.

And so my pilgrimage begins, walking west with an Irishman out of Pamplona.

V.

The sun above the valley beams brighter by the minute. My Osprey, bearable just hours ago, feels like it's doubled in weight.

“I think I packed too much shit,” I admit to Liam.

“Oh mate, I did too,” he replies. “Everyone does.”

“They say first-timers pack their fears. Probably why there’s a massive pile of discarded gear at the first albergue in Rocenvasailes. You should have seen it: boots, Birkenstocks, sweaters, hair dryers, beard trimmers — even a bloody rice cooker. After the first day of walking everyone realizes the non-essentials aren’t worth the burden.”

At a glance, Liam’s bag looks a couple bricks heavier than mine. When I ask why, he tells me it has to do with the jeans, Stan Smiths, and polo shirts he packed last minute for the nights out sampling vino tinto at tapas bars in the bigger cities. A bachelor myself, I can’t blame him for the vanity concerns. That he brought along party clothes is, however, hilarious given the toll the extra weight’s now taking on his feet. Like idiots we laugh about this as the absurdity dawns on us both.

***

By noon we’re sweat-drenched and dusty, swapping cornerstone details that make up our lives.

Liam’s a doctor in the ER, or, at least, was a doctor in the ER. The last few years were long and punishing, and left him with what he’s pretty sure is PTSD. He tells me about the night shifts and panic attacks; the webcam goodbyes.

Through it all, he’s not sure if the medical path is right for him anymore. Now he has to figure out if he wants to return home to Ireland, close to his mom and sister, or take a chance on another part of the world, maybe Thailand or New Zealand. Liam’s got a few months before these questions come to a head, so he’s taking some time for himself to mull them over. A little active solitude to ponder where he’s been and where he’s heading next.

“Figured I’d walk across Spain,” he says, not masking a proud, bewildered grin.

A few kilometers later, we break for chorizo and trail mix under the awning of a low-hanging oak tree.

I tell Liam how I used to live in New York City but fled to the suburbs, back in with my parents, when the cases first spiked. How I remember turning thirty that March, two weeks after lockdown started; and how strange it’s been ever since, all that time in front of a screen, pushing through boredom and loneliness, fending off apathy, strumming my guitar.

I explain that my decision to walk the Camino came on a whim, after a job interview, just two weeks earlier.

It would have been a decent gig. I could have moved back to the city, reclaimed a semblance of my pre-pandemic life. But something about it didn’t sit right. I tell him it had to do with the way the guy interviewing me kept hammering the company’s “eat-what-you-kill” compensation structure, and how they wanted to make sure I’d be able to thrive in that kind of environment.

Listening, Liam unlatches the blade of a wooden Swiss knife and begins to carve the chorizo in quarter-size slices.

I go on, explaining that the Way had been on my mind for some time, and that after that call ended I knew I would do it. How I realized the urgent pinging of emails, deadlines, and earning charts wasn’t going anywhere; how I could practically hear the older version of myself pleading with me to book the flight, to experience some life again first, beyond the veil of a screen or bubble or comfort zone.

As my monologue comes to an end, it strikes me how trivial this all must sound to Liam in light of what he experienced in the emergency room.

“Jesus,” I say, scoffing at my own expense. “How’s that for a litany of first-world problems?”

Rather than pass judgment, my hours-old friend hands me what’s left of the chorizo.

“We all suffer in our own ways, mate.”

VI.

After lunch, the Way winds us through fields of dried sunflowers and towering hay bales. We’re hot and tired but the conversation flows easily. We chat about The Beatles, our lapsed Catholicism, and the lectures of Alan Watts. Liam tells me he’s been reading up on Buddhism and the Eightfold Path.

“The Buddha perceived an impermanence to everything,” he says. “That we live, die, and are reborn in cycles.”

“Do you know what Buddha means?” He asks me.

“I do,” I say. “Awakened one.”

“He was a real person you know,” Liam says. “A renounced Prince named Siddhartha Gautama, lived five hundred years before Christ. Bit of a pilgrim himself, come to think of it. Wandered across India preaching this new understanding of the world, this idea of the Four Noble Truths.”

Passing a crumbling monastery, we trade nods with a trio of shirtless Italian pilgrims breaking for coffee and hand-rolled cigarettes.

“The first truth,” Liam continues, “is that suffering is part of life. Second - suffering is caused by craving and attachment. Third - inner peace is attained by extinguishing craving and attachment. And the fourth,” he adds, “is that liberation from suffering is possible by following the Eightfold Path.”

Wrestling with the irony of discussing Buddhism on a Catholic pilgrimage, where suffering is not only expected but embraced — even considered redemptive — I ask Liam what he makes of it all, these conflicting understandings of God. Whether he believes there’s an impermanence to everything, or if he wagers there’s something more to it.

“I dunno,” he says, ruminating on the notion. “I reckon those kinds of answers come from inside us. To claim otherwise is a bit like reading a menu and pretending you’ve tasted the food.”

In the meadow to our right a cluster of wildflowers sways delicately in the breeze.

VII.

Five hours after leaving Pamplona, we arrive at the onset of Alto del Perdón - a gradual ascent snaking its way up a mountainous ridge. Cutting across the ridge, a row of colossal white wind turbines breaks through the clouds, their blades spinning like spires of a higher kingdom.

Consulting Brierley, I learn that at 750 meters high the Hill of Forgiveness marks the apex of today’s trek. Eyeing the incline, Liam and I shoot each other the same dispirited glance. “Your feet gonna survive this?” I ask, half-kiddingly.

“I’ll manage,” he says, pausing to tighten a gauze bandage behind his right sock.

Under the droning hum of the whirring turbines, I swig water from my bottle and let some splash out down the back of my reddening neck. Liam’s ready now.

“My father was a foreman,” he tells me as our trudge up the hill begins. “Ran a small crew. Mainly home renovations. Floorings, remodeled kitchens, things of that sort. In the summers, though, they did a lot of roofs.

“One day, wrapping up a job, the ladder he was on slipped on an oil patch from underneath him. They told us it wasn’t a long fall, didn’t look so bad at first. Only awkward. But his head smacked the pavement when he landed. Knocked him out cold.”

I glance Liam’s way to let him know I’m listening.

“For eight days he was in a coma,” he says, returning my glance. “And then he passed.”

“Christ,” I say. “I’m so sorry to hear that.”

“It was a long time ago,” he says, powering up the hill unfazed. “I was twelve at the time, my sister was nine.”

“Twelve and nine are tough ages,” I say.

Liam nods like he knows this already.

“Back when it happened I put all kinds of pressure on myself to be this man of the house stand-in, but of course at the age you’re just not equipped. For the longest time I couldn’t even cry about it. Pushed most of that grief down to carry on. I was a shy kid before the accident, and even more so after, but I kept good marks in school.”

“And you became a doctor,” I say.

Liam almost laughs. “A therapist once told me that she figured I took up medicine as a way to gain control over the chaos of tragedy at that age. Imagine that? If I couldn’t go back and stop my dad from dying, then maybe there was a kind of healing to be found in saving others.”

“Did you agree with her?” I inquire, my shins now flaring with each ascending step.

“At first, no,” he says. “But I suppose it makes sense now.”

“And what about the chaos part?” I ask. “You gain any control over that?”

Gazing at the turbines looming higher atop the hill, Liam's face again turns pensive.

“Back in med school I volunteered for a summer in Bogotá,” he tells me. “The last week I was there, last week of the program, a couple of my mates talked me into joining them for an ayahuasca ceremony in the Amazon.”

“How’d that turn out?” I ask, my curiosity piqued.

“Well. It was powerful,” he says. “I had what you’d call a mystical experience. At first I didn’t think anything was happening, figured I didn’t take enough.

“We’re sitting there, ten of us or so, round a circle of sleeping pads under the thatched roof of this screened-in hut in the middle of the jungle, and we had all just drank a clay mug of this stuff, this tannic-tasting brew. There was this shaman in the middle burning bundles of sage and palo santo wood. His face was primordial looking, like it was molded from clay. I remember he had these deep green eyes, a gray braided beard, and this necklace made of bones and shells that shook like a tambourine as he shuffled around the room. You’d think he was frightening, ya know, but he wasn’t. He was like a granddad.

“Anyway, he starts tapping this slow hypnotic pattern on a hand drum made of hide. Sounded like the heartbeat of something ancient, eternal. Around me a few folks start purging, puking into buckets. A sign of cleansing they tell you, that the medicine is starting to take effect. Others were sitting perfectly still. But my mind’s racing and so is my heart rate, and I don't know what to expect. So I fixate on the beat of the shaman’s drum and try to breathe slowly. And at one point he locks eyes with me and drifts over. He’s mumbling something under his breath that I can’t make out until he’s right up against my ear. And then I hear it. ‘Surrender,’ he’s saying. ‘Surrender hermano.’

“And then, as if gradually and all at once, I emerged in a memory. There I was. Ten again. Hiding on the stairs that ran from my room above the garage down to where my dad’s workbench used to be. Where he liked to tinker with projects after putting us down for bed. He’d fix stools and benches, build flower boxes, birdhouses, things of that sort. Often he’d play records and permit himself a whiskey while he worked.

“And on this night, in this moment, he had dropped the needle on The Joshua Tree. He was keen for U2 in those days, especially that album. Crackling through the speakers comes the organ intro of Where The Streets Have No Name. You know the one, don’t ya? Starts like a church hymn with that shimmering guitar build.”

“Sure,” I say. “I love that song.”

“Right. Well I’m watching my dad between the stairs. He’s got his eyes shut with the softest uptick of a smile, and he’s swaying to the music, utterly entranced. My father was never an expressive man, so witnessing this was a revelation of sorts. A couple minutes pass and I’m still watching, enamored, when I hear him call out my name.

“‘Liam lad, are you listening?’ he shouts, sending a jolt through me on the stairs. ‘This one’s about heaven.’

“And when he says this the room, the memory, all of it, shatters into fractals of piercing white light. Brilliant, geometric patterns of light. I could hear the shaman’s drum but I was far from it. I was sailing through a liminal place, cradled in the arms of an immense presence. And I could feel my dad’s energy emanating from it. I couldn’t see him but I swear it was like he was right there again. Sitting at his workbench, swaying to the music, calling out my name.”

As if he still can’t believe the memory himself, Liam slants his head sideways and appears to withdraw inside himself.

“Suddenly, like I had woken from a dream, I was back in my body, back in the hut, rocking like a child back and forth. And the shaman was holding my hand, gripping it tight. And there were tears streaming down my face faster than I could wipe them away. Because something inside me had cracked. All that grief, shoved down and calcified. Mate it was rushing through my pores like a spirit set free.”

Liam glances my way, his eyes wide with a glint of wonder.

“I could feel the weight of it leaving.”

***

Nearing the summit, we pause to peer back upon the valley we came from. The view is expansive and beautiful and clear.

“It’s an amazing story,” I say.

“Words can’t do it justice,” he assures me. “But I reckon there are forces of this world that exist beyond our capacity to understand them. Using language to describe what I encountered that night is simply inadequate.”

“Like reading a menu and pretending you’ve tasted the food,” I suggest.

Liam’s smirking again, shaking his head.

“Something like that,” he says, pulling off his glasses to wipe away the fog.

VIII.

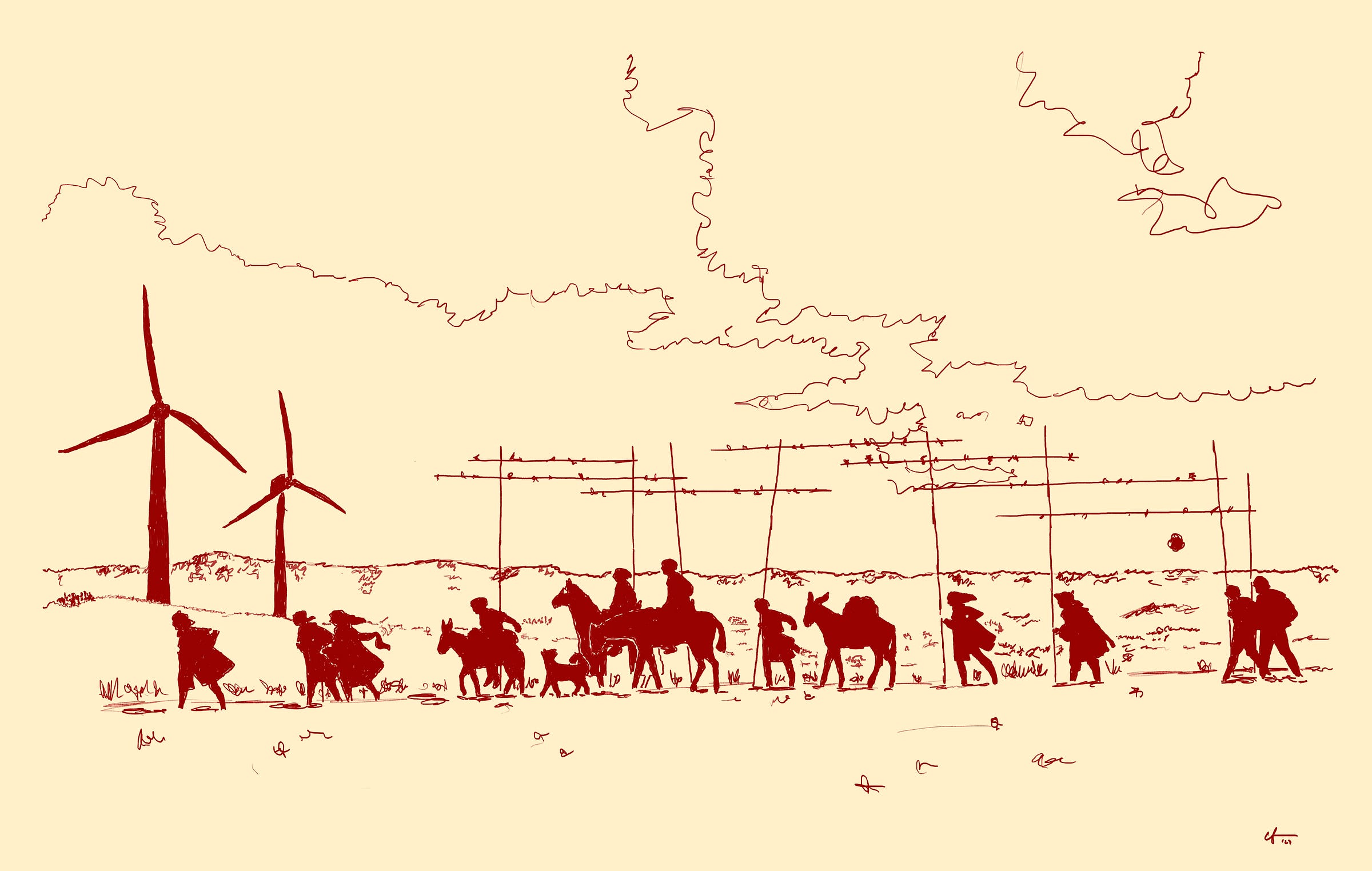

Greeting us atop the windy peak is a wrought iron statue of considerable size. The structure depicts a caravan of twelve faceless pilgrims slanted forward, heading west. Among the twelve, two are on horseback, two lead donkeys, a leashless dog looks back. Like cardboard cutouts they appear to be frozen in time.

Liam needs to rebandage his feet, so I wander over to the statue to examine the rusted-orange figures up close. Around them, several flesh-bound pilgrims snap selfies, drink water, and stretch. One of them is Beth, a retired art teacher from lower Manhattan.

“Can you believe we signed up for this fucking thing?” she says, cackling in exhaustion under the brim of her camouflage trucker hat. We share a laugh the way stray Americans abroad do to feel more at ease in unfamiliar places.

“What’s the story behind this?” I ask, gesturing to the statue.

“It’s a procession,” she says, reading from an app on her phone, “representing a history of pilgrims from the Middle Ages to the present day.”

She aims her finger at the front of the statue and moves it down the line as she reads.

“The first figure is shown seeking the way, symbolizing the early days of the pilgrimage. The group of three that follow indicate a rise in the Camino’s popularity. The two tradesmen on horseback mark the Medieval era of merchants hawking their wares upon pilgrims.” Beth clicks her tongue. “Grifters.”

“Farther back is a solitary figure, signifying six hundred years of decline due to political and religious unrest. Ah, and how interesante,” she adds, pointing to the back of the procession.“ At the tail end are two backpacked figures—modern pilgrims—representing the surge of renewed interest in the Camino in the late 20th century.”

“That’s us, huh?” I say.

“That’s us,” she says, waving her iPhone like it’s contraband. “Only we have Google Maps.”

I thank Beth for the lesson and look back to check on Liam, watching as he cuts gauze and tears strips of tape with his teeth, wrapping each blistered foot with paramedic precision.

Before leaving, I notice an inscription, a Spanish phrase, etched on the center-most figure’s horse. Donde se cruza el camino del viento con el de las estrellas, it reads.

“Hey Beth,” I say, “do you know what this means?”

Beth lowers her aviators and squints.

“Donde se cruza el camino del viento con el de las estrellas,” she says, reciting the line in halfway-decent Spanish. “Where the path of the wind crosses with that of the stars.”

***

Liam and I descend sharply and carefully over loose stones, and then the land is flat.

For two more hours the Way runs parallel to a quiet country road, meandering past almond trees, vineyards, and acres of untilled farmland. We walk mostly in silence. By now the sun has called a truce with the day and the sky is tinted gold in every direction around us. On the horizon a stone steeple juts out above the trees, its iron bells look like embers glittering against the refracted light.

“Puente la Reina,” says Liam.

IX.

Liam and I take our spots in line in front of a rectangular building that looks like a cross between a barracks and a college dorm. When we reach the entrance a team of two cheerful Spanish women, volunteers who look to be in their late sixties, ask for nine euros and our pilgrim’s passports. The paper passports contain our names, country of origin, and starting points. Doubling as a stamp book, the passport stretches out like an accordion with several pages of empty slots. One of the volunteers gives me my first stamp: a light blue crucifix on the crest of a scallop shell. ALBERGUE REPARADORES, it reads, PUENTE LA REINA NAVARRA. It is the first of over forty unique imprints I'll accrue from here to Santiago.

With my passport freshly stamped, I’m handed a plastic-wrapped bundle of disposable bedding - a pillow case and mattress cover, merely sanitary veneers to wrap around the bunk I just paid for.

The scene in the albergue is like a summer camp. Pots and pans clink and clatter from a communal kitchen as spaghetti is dished around long wooden tables. Red wine is poured in paper cups. The age range, I notice, spans wide. College grads break bread with pilgrims old enough to be their grandparents. A babel of language fills the air. Spanish, French, Korean, German, among others I can’t discern.

After whisking off our footwear and dropping our poles in the lobby’s mudroom, Liam and I slip into sandals and are ushered upstairs to a room of eight synthetic blue bunk beds. The bottom bunks are already accounted for, so we take what’s left in the top middle row. Told you so, Liam’s wry expression implies. But we’re both too tired to care. Setting down my bag, I grab what I’ll need for the night - a feather-lite sleeping bag, body wash, quick dry towel, joggers, and a white t-shirt.

For a few awkward minutes I wait in line for a shower, standing half-naked in what amounts to a microfiber loincloth as a procession of strangers shuffles by. Once in, a silver button triggers the old shower and I am hit with a torrent of cold, unbelievably refreshing water.

Rejuvenated and changed, I wander back downstairs to hand-wash my laundry in an industrial sink. On the lawn outside, perched along the bank of a gentle river, clusters of pilgrims hang clothes on crowded lines. There’s a group doing yoga. Others sit by themselves, reading, smoking, airing their feet. A man with blond dreadlocks plucks chords on a plastic guitar. I’m not convinced my clothes will be dry come morning, but I hang them up anyway to catch what’s left of the dying light. On the grass I stretch my heavy legs, and journal for a bit.

I’m learning that this will be a mental battle as much as it will be a physical one, I write—one fleeting thought amidst a thousand other insights—Important to take it one day at a time.

By the time I head back upstairs to see if Liam wants to join me for dinner in town, the room is dim and quiet aside from a few rumbling snores. My lone acquaintance is burrowed under his sleeping bag, orange earplugs jammed in his drums, out like a light.

X.

In the dark morning, a one-lane road leads pilgrims out of Puente la Reina. Treading over its cobblestones, I hear espresso machines hiss from amber-lit cafes. A stray dog saunters by. I spot Beth sitting for coffee and an egg tortilla and wave to her as I pass. Here we go again, her bemused eyes seem to say.

Around me headlamps flicker and flash. They look like fireflies, glowing in the twilight, dozens of them, swarming over that old Roman bridge that Brierley wrote about. Built to support the safe passage of an expanding number of pilgrims hoping to cross the powerful rio Argo. Nearly a thousand years later it is serving that purpose again.

I better get moving, I think. Fourteen miles to Estrella. Today will be another hot one. Another quiet stage along gently rolling farmland and vineyards with few trees and little shelter. I’d be wise to heed my Irish friend’s advice, try and beat the worst of the heat early.

Liam stayed back this morning. He’s going to rest for a day or two, buy himself a new pair of shoes, give his blisters the time they need to heal. The Camino, after all, is a marathon, not a sprint. And he plans to finish it.

In the albergue’s kitchen we exchanged numbers on WhatsApp and vowed to keep in touch. Perhaps our paths would cross again, maybe in Burgos or León. But we wouldn’t count on it. And that was okay.

Before stepping out, I thanked Liam for the trail wisdom, and wished him well.

“Nick from New York,” he said, meeting my eyes as we gripped hands goodbye.

“I’ll see you on the Way.”

Found this through story club, thanks for sharing!

What an absolutely wonderful story Nick. I feel like i traveled with you, eavesdropped into your conversations both those through your ears and through your mind. I do hope you'll give us more stories of this transformational time..lots more through these paths few of us will walk. Please?